Equi-note 15 Hyperflexion-rollkur causes extensive physical and mental damage

Source: 1st photo: pi; 2nd & 3rd photos: nkc;

Equi-note 15

Hyperflexion-rollkur-causes extensive physical and mental damage

The previous posts have shown that hyperflexion-rollkur has a very long history. Even though its damaging welfare aspects were not recognized as such. Any health issues which would have arisen were swamped by the needs, usually for cavalry and being battle prepared.

Contemporary society and its different values has meant that concern is now given to the numerous prejudicial consequences on the horse. The heated debates surrounding its use confirm that it is a complicated subject and one which requires in-depth attention.

In addition to the use of horses in the military, detailed attention was not so significant in previous centuries, given the rudimentary state of medical/veterinary knowledge.

Welfare concerns are a product of modern-day societies. Which today must be respected and integrated into horses’ training and well-being. Consequently, analyses of how rollkur affects the horse need to be made. Later posts will be made across a range of aspects where the horse is affected.

This post will look at several of the leading issues which are the neck, the poll and the stomach.

Recent history of rollkur

By way of recent background, Equinamity believes it is essential to point out that the rollkur problem came to international prominence in the 1970’s. However, for several decades even before this time, it had been used in a more anonymous format by a number of well-known trainers. But from the 1970’s onwards it was used by several Olympic showjumping riders which gave it a more prominent public profile. This was followed by its use with several very successful dressage riders winning Olympic medals. Consequently, this set in motion a “copycat” trend which was imitated by thousands of aspirants looking for equestrian success. It is a situation which created widespread damaging consequences.

Role of the FEI

The official body with a virtual monopoly on overseeing horse welfare in important competitions is the FEI. Public comment on the quality of their advice on this subject has been highly negative. Subsequent to intense pressure, a revised FEI Steward’s Manual was implemented in 2010 which took into account some of these concerns, but which simultaneously created new ones. The main one is a fudge using a so-called LDR/Low deep and round head and neck position.

Consequently, the question needs to be asked why it took 20 years for action to be taken on such a problematic issue by the presumed authorities? And during this time the issue of hyperflexion-rollkur has been fudged with a nonsensical LDR head and neck position which is treated with scepticism by many riders and trainers.

And how successful have the 2010 rules been? Clearly, these are helpful steps, but they do not go far enough to eradicate the training method. A contributing factor has been pressure from vested interests.

This controversy prolongs the problem for the horse and worsens the public’s perception of horse sports. For the well-being of both horses and the sport it is essential the the FEI resolve this matter on an objective basis which satisfies the requirements of all interested parties.

The impact on the horse’s physical and mental health will be looked at next.

Hyperflexion-rollkur-causes extensive physical and mental damage

Neck

There are many things that can go wrong with this important part of the horse’s anatomy. In the bones, muscles and ligaments. But when unnatural positions are demanded of the horse, it is inevitable that negative consequences arise. One of these is looked at next.

Osteoarthritis

This analysis will start by a review of osteoarthritis in the neck. The analysis is not exclusively the outcome of rollkur, but it points in the direction in which damage can occur. By looking at the three main movements it is possible to identify where stresses are likely to emerge in the cervical vertebrae.

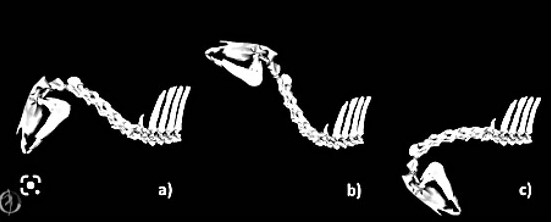

The following image shows the three main positions of normal, extension and flexion.

a) normal b) extension c) flexion

Source: “Equine neck and its function during movement and locomotion” Zsoldos, et al 2010

The following quotation analyzes equine cervical pain in greater depth:

Equine Cervical Pain and Dysfunction: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment”; 2021: by Melinda R. Story, Kevin K. Haussler, Yvette S. Nout-Lomas, Tawfik A. Aboellail, Christopher E. Kawcak, Myra F. Barrett, David D. Frisbie and C. Wayne McIlwraith, Orthopaedic Research Center, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA:

“Cervical Articular Process Joint/APJ Synovitis and associated joint pain are commonly diagnosed as a cause of poor performance in horses. OA/Osteoarthritis is a disease of the cartilage surface and bone structure; however, it is important to recognize that other structures within the joint complex, which include subchondral bone, joint capsule, synovium, and paraspinal muscles, are also affected and can be a primary source of cervical pain. Radiographic evidence of OA of the APJ includes joint enlargement, subchondral sclerosis, extension of the dorsal laminae, joint margin lipping, and the presence of osteophytes and joint capsule enthesophytes.

Most common noted bony changes

A recent post-mortem study in a mixed population of horses showed that the most commonly noted bony changes on the caudal articular processes were modelling and joint margin flattening, while the most common changes noted on the cranial articular processes were osteophyte formation, joint margin lipping and enthesophytes of the joint capsule with the most severe changes noted at C2-C3 and C7-T1.

Interestingly, a retrospective study found that the C5–C6 APJs are enlarged with no correlation to clinical signs and it has been reported that approximately 50% of normal mature horses have some degree of unilateral or bilateral changes in cervical joint margins. These findings make it impossible to diagnose cervical pain or dysfunction solely based on radiographic images and caution should be used to avoid the overinterpretation of OA as the primary cause of the observed clinical signs.

Osseous proliferation of the articular processes is reported to cause a wide variety of clinical syndromes in horses

They show up depending on the presence of local, peripheral or central effects. Locally, direct mechanical and inflammatory effects on cervical motion can produce signs of neck pain, muscle atrophy, stiffness in a specific direction, resistance to induced joint motion (e.g., baited stretches), and pain on palpation.

Abnormal head and neck carriage may also occur if the upper cervical vertebrae are affected

Peripherally, osseous proliferation has been reported to mechanically compress or chemically irritate the cervical nerve roots exiting the intervertebral foramen. This can produce signs of neck pain, local sweating, muscle atrophy, reduced performance, stumbling, and obscure forelimb lameness. Centrally, changes in the articular process size, shape, and spatial orientation are commonly reported to change the internal contours of the vertebral canal. They also contribute to cervical myelopathy, which often produces signs of ataxia, paresis and spasticity that are typically more pronounced in the pelvic limbs, compared to the thoracic limbs.

Topographically, osteoarthritis is not distributed evenly throughout the vertebral column. Osteoarthritic changes are most commonly localized to the 5th, 6th and 7th cervical vertebrae and can occur in both young and old horses. With a current resurgence of training horses in extreme head and neck positions in both English and Western disciplines there is risk for induced joint disease throughout the entire cervicothoracic region (i.e., occiput to T3).

The severity of bony changes varied across vertebral levels

The highest prevalence of mild changes was localized to the C3-T2 vertebral levels; moderate changes at C6-T2; and severe changes were noted more commonly at C2-C3 and C6-T2

The directions (e.g., flexion-extension) and ranges of joint motion that normally occur within the cervicothoracic intervertebral articulations are likely to affect the prevalence, location within an articular process, and the severity of osseous lesions. Osteoarthritic changes within the cervical region have been most commonly reported at the C5-C7 vertebral levels. In our study, we found a large variety of different types of bony changes distributed from C2 to T3. Osteophytes were more prevalent at C6-T2, but also had a similar prevalence of 30% at C2-C3, which corresponds with the cranial and caudal extremities of the neck that undergo large ranges of joint motion and which may incur an increased risk for microtrauma in horses with constrained (e.g., draw reins) or chronically-induced and repetitive excessive head and neck postures.”

Nuchal bursa

The second condition to be looked at is the effect of hyperflexion-rollkur on the poll. However, the level of association of nuchal bursa with rollkur remains to be quantified.

Wikipedia states the following: “Poll evil is a traditional term for a painful condition in a horse or other equid. It starts as an inflamed bursa in the cranial end of the neck between vertebrae and the nuchal ligament, and swells until it presents as an acute swelling at the poll, on the top of the back of the animal’s head. The swelling can be caused by infection but may also occur due to parasite infestation, skin trauma, striking the head against a low clearance structure, badly fitting tack or improper use of equipment”.

A further description from an anatomical stand-point is explored in the next quote:

Dippel M, Zsoldos RR, Licka TF. “An equine cadaver study investigating the relationship between cervical flexion, nuchal ligament elongation and pressure at the first and second cervical vertebra”. Vet J. 2019 Oct;252:105353. doi: 10.1016 /j.tvjl.2019.105353. Epub 2019 Aug 7. PMID: 31554589.

“Pressure in the atlanto-axial region due to hyperflexion (‘rollkur’) may influence the development of a nuchal bursa, as adventitious bursae may be caused by pressure. Investigating the pressure between the nuchal ligament and atlas/axis in a flexed position may provide information on the pathogenesis of nuchal bursitis. In this study, ten equine head and neck specimens with one side of the soft tissues over the cervical vertebral spine removed were placed in lateral recumbency on a table in neutral, mildly flexed, and hyperflexed head and neck positions. Angulations of the neck were measured using markers placed on the nuchal ligament and drilled into the skull, vertebrae and withers. In six specimens, the pressure between the nuchal ligament and the atlas and the axis was measured using an inflatable air pouch.

Hyperflexion was associated with the highest nuchal ligament length and with the highest-pressure values at the site of the nuchal bursa over the atlas (99±24mmHg, more than four times the pressure in the neutral position) and over the axis (77±30mmHg, more than twice the pressure values of the neutral position). Also, over the three head and neck positions, neck flexion angles were highly correlated with pressure values and with nuchal ligament length. This marked increase in pressure at the level of atlas and axis caused by head and neck hyperflexion should be considered during training of horses at risk of, or diagnosed with, nuchal bursitis.

Pressure in the atlanto-axial region due to hyperflexion (‘rollkur’) may influence the development of a nuchal bursa, as adventitious bursae may be caused by pressure”.

This finding is valuable and contributes to the pool of knowledge about this condition. For the sake of overall horse care it is important to underline that this issue was brought to the public’s attention as a risk by German veterinarian, Dr. Horst Weiler in his book “Insertionsdesmopathien beim Pferd” published in 2000. His work focussed on illnesses in and around the attachments of tendons and ligaments in horses.

In his studies, he found that 80% of horses used for dressage and jumping had injuries around the attachment of the nuchal cord on the head. Horses used for hacking, trotters, ponies, coldbloods, had these injuries to a much lesser degree or not at all.

In spite of this important work being available numerous researchers on the subject of rollkur have ignored its implications for many years.

These are the first comments on this subject which will be looked at in greater detail in a subsequent post.

Illustrations of this condition follow.

Nuchal bursa-“poll evil”

Source: wikimedia.org, 1906. pd

Ulcers

A third area where hyperflexion-rollkur can cause damage is via stress.

The subject of stress will be looked at in greater detail in subsequent posts since a number of other issues are intimately involved, such as heart rate, cortisol, blood lactate, etc. All of which have a significant bearing on the horse’s physical and mental state.

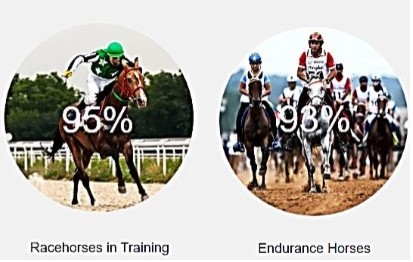

As has been mentioned, stress can arise from many different situations where the horse is subjected to a variety of performance demands. One of most common consequences is by the creation of ulcers. And their frequency is much greater than is generally appreciated. The following image shows that this condition happens across a wide range of activities.

Prevalence of Gastric Ulcers

Source: randlab.com. wp

The following quote provides further detail on symptoms and causes of this condition.

“7 Common Causes of Gastric Ulcers in Horses” by Dr. Priska Darani, Ph.D. for Mad Barn.com, 2023:

“Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS) occurs when sores develop on the lining of the horse’s stomach. The physiochemical barrier that usually protects stomach tissue is worn down and digestive acids cause painful lesions in the stomach’s lining. This condition is known to affect 60-90% of performance horses particularly when travel, high-intensity exercise and long periods without feeding occur. It also occurs at high rates in pleasure horses and young foals.

Research shows that any horse that undergoes stall confinement, has inconsistent access to feed, is fed grain or concentrates, or is trailered is at risk of developing ulcers.

Ulcers are painful sores that can occur along the entire digestive tract of horses but appear most commonly in the stomach and to a lesser extent in the hind gut. Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS) is a scientific term that describes horses that have ulcers in their stomach.

The stomach has two main sections, which are the upper squamous region and the lower glandular region. The squamous region is particularly prone to ulcers developing.

Equine Ulcers: Signs & Symptoms

Some common symptoms include:

Poor appetite or “picky eating”

Poor body condition or weight loss

Chronic diarrhoea

Poor coat condition or a rough coat

Bruxism or teeth grinding

A more aggressive or nervous disposition

Increased stereotypic behaviours such as cribbing

Acute or recurrent colic

Poor performance

Sensitivity in the girth area

Excessive recumbency

Stretching to urinate

What Causes Equine Ulcers?

Diet and Feeding

High Grain Consumption

Intensive Exercise

Intermittent Access to Water

Physical Stress

Social Environment

Anti-inflammatory drugs”.

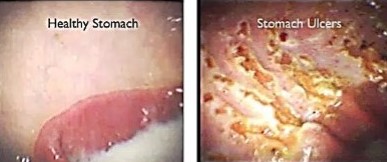

Healthy stomach vs ulcers

Source: www.randlab.com, wp

The above conditions are an introduction to several of the main issues affecting the horse’s health associated with hyperflexion-rollkur. At no time is the author suggesting that they are the exclusive cause; but they can be and are contributors.

The extent to which individual horses are affected will depend on a series of factors, which will be explored in subsequent posts.