Equi-note 24 What is rein pressure?

Rein tension or pressure is a complicated subject. It arises from two overall forces: the rider’s hands and the horse’s mouth. The reins are the connectors between them and at times are complementary and times conflicting. It exists because the rider needs to control, and the horse needs to move. It has an infinite number of variations as will be described in this post.

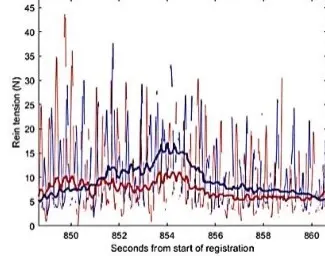

High frequency and highly variable rein pressure is shown next. Data is taken from a trotting racehorse, where this pressure varies from 2 Newtons to 44 Newtons within the space of a fraction of a second.

Rein pressure on a trotting racer

Note: left rein/red and right rein/blue show median rein tension in newtons/n. (1 kg/weight equals 9.8 N/force).There are approximately ±36 peaks in 12 seconds, or ±3 peaks per second.

Source: “Associations between driving rein tensions and drivers’ reports of the behaviour and driveability of Standardbred trotters”; by Elke Hartmann, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, Department of Animal Environment and Health, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 75007 Uppsala, Sweden, et al. 2022:

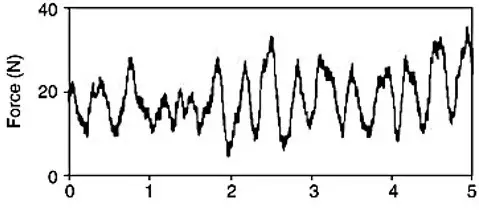

The next case shows rein pressure on a riding horse, where the variation exists between a minimum of 5 Newtons and 35 Newtons.

Comparing these two charts, show that in the case of the riding horse, the extremes are within a much narrower band (mostly in the 15-25 N range). The figures show only the left rein at the trot.

Rein pressure on a riding horse

Note: Measurement of rein tension riding-left rein at trot; ±3 peaks per/sec

Source: “Rein tension during horse-back riding activities”; by Wesley H. Singleton, 2001, MSU

Equi-note 24 What is rein pressure?

The above charts show very rapid fluctuations in the levels of rein pressure. These fluctuations are proof that to attempt to assign a single figure to rein pressure in each gait is meaningless. This is because these variations are extremely significant, both in the amount of pressure and in the speed with which they change.

As the above images show, these changes occur as much as three times per second. However, what is not linked is the fact that the pressure change occurs with every step. Other factors influencing rein pressure include the different gaits, the level of impulsion and collection.

In a more general sense, they are also greatly influenced by the type of activity being undertaken. Even unridden equine activities such as agriculture and driving are affected.

A range of activities is listed next which shows the extent of potential pressures involved.

- Purpose-pleasure, cavalry, racing, high level training, competitions

- Style-Western, English, other

- Riding conditions-road, arena, mud, slippery, hard, grass, flat, hilly, mountainous

- Type of bit-curb, snaffle, hackamore, double bridle

- Artificial aids-draw reins, side reins, check reins, noseband

- Rider-weight, balance, coordination, skill, fitness

- Horse-level of training, balance, coordination, soundness, fitness

- Work-level of fatigue of horse and rider, duration of ride

- External-distractions, other horses, dogs, sounds, smells, wind

Why is it important to analyse the level of rein pressure?

The most obvious reason is for the benefit of horse welfare. The second reason is for the benefit of the owner, rider and handler for purposes of control. As a result, the reason for analysing rein pressure is because it is essential to find a way to balance rider control with horse welfare.

There have been in the past and continue today to be many instances of excessive rein pressure. They leadss to various physical problems as well as serious disobediences.The previous post reveals the extent of the damage whcih can be inflicted. A frequent and unfortunate expression occurs when mouth damage occurs in public at horseshows.

Many members of the public are unaware of the actual effects of excessive rein pressure and its negative affects on the horse’s welfare. This may or may not be an entirely accurate perception. Where it is visible, say by the presence of blood, it has created a damaging public impression of equestrian sports. This must be corrected and thus a solution needs to be found. The best long-term solution is one which encourages better use of the reins.

As of now, a solution has not yet been found. Most of the studies conducted on this subject only go so far as to describe an actual level of pressure and state that horse’s welfare could be improved if “excessive” pressure were avoided. This is wishful thinking which is imprecise and unhelpful.

It is obvious that this is not a satisfactory outcome for riders, trainers and especially for horses. Because it does not provide the appropriate tools they can utilize to both improve their activities while also improving their horse’s performances. Equinamity has developed a revolutionary new solution to this problem. It will be described in detail in later posts in this blog.

However, to appreciate more fully the complexity of the rein pressure issue, it is essential to explore the current knowledge level which exists amongst researchers. Consequently, in several posts, the current status will be investigated based on published studies. The main focus will be to look at the rein tension in two of the main equestrian activities of jumping and dressage.

These studies have analysed rein pressure for both ridden and unridden horses, on treadmills and on the longe and with a variety of different rein types.

What is the right rein pressure? General comments follow

The most important operative principle is that reins are loosened to make it easier for the horse to go forward and shortened to make it brake/stop/slow/turn.

There are many different aspects to rein tension, including:

- Excessive rein pressure produces a range of negative effects on the horse.

- Rein pressure negatively affects its performance (mobility, visibility), its physical functions (breathing, blood circulation, tooth damage), and its psychological well-being (disobediences, condition).

- Reins are short and often tight for jumping and dressage.

- Reins are loose for trail riding but harsh at moments of braking.

- Rein length is alternately loose/tight for carriage horses; and may be combined with check reins for showing purposes.

- Check reins are often used with trotting racers.

- Auxiliary reins play an important role in the level and type of tension.

- The right level of rein pressure combines firmness with softness.

When is rein pressure excessive?

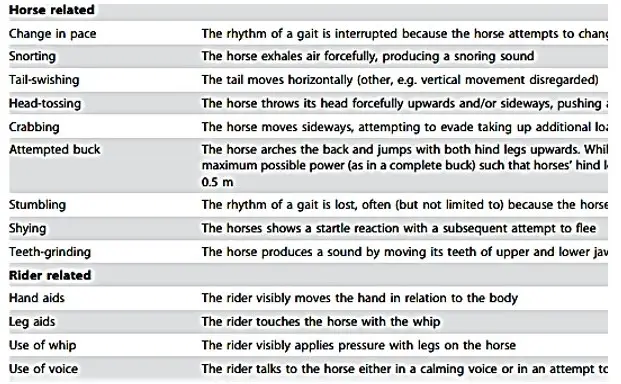

Rein pressure is excessive when it forces the horse to do something it either can’t or won’t do. There are many degrees of opposition. Excessive rein tension forces the horse into a number of defensive actions. These have been identified in ethograms which have been quoted in previous posts.

A summary is shown next.

Actions symptomatic of excessive rein pressure

Source: “Alternatives to Conventional Evaluation of Rideability in Horse Performance Tests: Suitability of Rein Tension and Behavioural Parameters”: by Uta Konig von Borstel*, Chantal Glißman, Department of Animal Science, University of Gottingen, Gottingen, Germany, 2014.

When is rein pressure insufficient?

The most obvious signal is when reins are floppy. However, in some forms of riding this is the natural state, especially if curb bits are used. When using a snaffle, a floppy rein indicates a loss of contact, which is not usually good. It also often ends up with the horse leaning onto the forehand which can lead to stumbling. It is also risks a run-out approaching a jump. A loss of contact can also be an encouragement to an exuberant horse to play up. Such as with a buck, especially on a frosty morning.

Between the two extremes of too much and too little pressure, there is a happy medium of a gentle but continuous contact with the horse’s mouth. Maintaining the right balance is not easy but it is an important goal to strive for.

How can the right level of rein tension be obtained?

An important guideline already mentioned above, is that as a consequence of its physical dynamics, the horse’s mouth, head and neck positions are in constant movement. This means that they are never fixed. By extension, this means that the rider’s hands must be continually responsive

The rider’s hands are at the other end of the reins. They are the reverse side of this same coin, which means that they too, can or should never be fixed. They will vary as a result of the many different conditions mentioned above.

The physicality of the horse is such that its motions are expressed across a wide range of actions. Both the action itself as well as its intensity will influence the extent of the head and neck movement. It is to all of these actions that the rider’s hands must adapt. They may range from a twitch of the fingers to the extreme of a full arm length pulling action reinforced by a backward leaning body and legs braced in the stirrups.

Failure to follow through with a measured, timely and coordinated rein response will lead to a rein blockage. As soon as the reins are blocked resistances will be created with the horse. Likewise, a reactive pull on the reins by the horse will immediately cause the rider to tighten the hand and arm muscles. Almost automatically this will lead to an escalation in rein tension.

Apart from being disagreeable for the horse and throwing the rider off-balance, it also has the unfortunate side-effect of biasing all studies since this causes an unwanted, unnecessary, temporary and very frequent increase in rein pressure.

What are some of the factors influencing rein tension variability?

The horse’s reactions to pressure on the mouth can be demonstrated in many ways, most usually by outright rejection, as shown by the head up/down/out and mouth open. It is also shown by submission with the head pulled in towards the chest or it can lower its head and lean on the bit (and sometimes buck, to get rid of the rider).

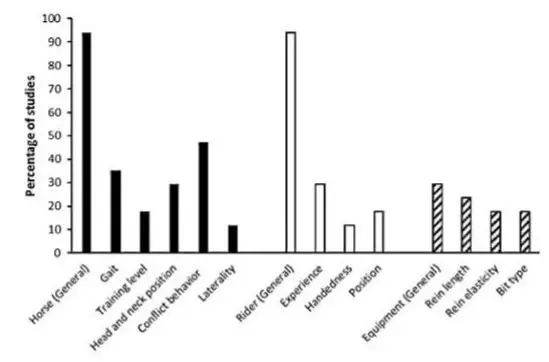

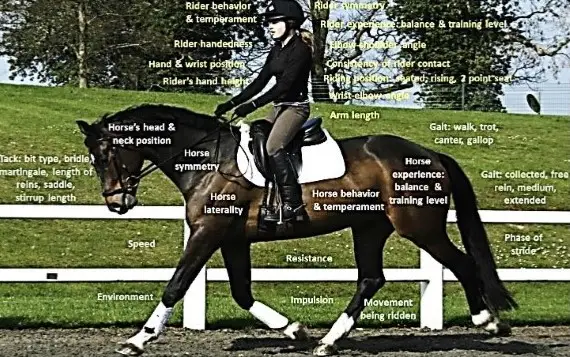

Resistances in both type and severity are linked to many things, including the level and type of training, quality of riding, tack and severity of rein pressure. The next chart shows some of the factors influencing rein pressure.

Factors associated with rein tension variability

As can be seen from this chart, general horse and rider factors are predominant, affecting over 90% of both horses and riders. These are looked at next.

Factors affecting rein tension in the ridden horse

Horse-rider-performance factors

Note: white text: horse-related factors; green text: performance-related factors: yellow text: rider-related factors

Source: “A systematic literature review to evaluate the tools and methods used to measure rein tension”; by Lucy Dumbell*, Chloe Lemon, Jane Williams, University Centre Hartpury, Hartpury House, Hartpury GL19 3BE, United Kingdom, 2019. doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2018.04.003, [email protected]

Range of rein pressure

In addition to knowing what rein pressure is, it is important to have an idea of the levels of force involved. Several studies have analysed this aspect of rein pressure, which are quoted next.

“A preliminary study on the relation between subjectively assessing dressage performances and objective welfare parameters”; 2005; de Cartier d’Yves A, and Ödberg FO*, Ghent University, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Animal Nutrition, Genetics, Breeding and Ethology, Heidestraat 19, B-9820 Merelbeke [email protected]; [email protected]; +3292647804.

“Inappropriate schooling is probably an underestimated welfare problem. Technology could help evaluate whether particular practices are stressful to the horse. In contrast to academic principles, supple and unconstrained gaits (‘lightness’) are not widespread in modern riding. Intensity of rein tension is one expression of it.

A high pressure on the mouth is usually an indicator of a stiff horse ridden with hard aids. However, some individuals could be more or less sensitive to that pressure, while others experience more or less pain due to hard leg or seat aids. Hence evasive behaviours might depend on each individual’s sort of sensitivity.

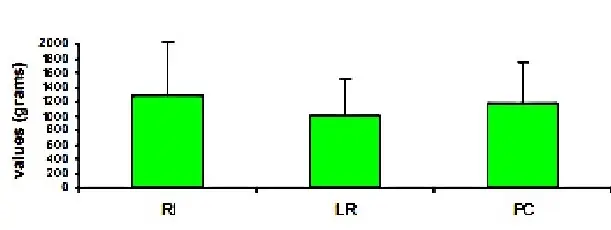

This study analyses right rein tension during a dressage test performed by three riders and 30 horses, including RI-riding school horses, LR-leisure horses, and PC- professional competition horses.

Results from the only horse that was tested up to now show that the average rein tension of this Lusitanian (339 grams) is much lower than that found in the present study (horse with the minimum average rein tension = 639 grams; average rein tension of the 30 horses = 1184 grams; horse with the highest average rein tension = 1930 grams)”.

Another study analyzed rein tension by type of riding. Three types were considered: riding, leisure and professional competition.

Average rein tension by type of training

RI-riding horse; LR-leisure riding; PC-professional competition

Source: “Rein tension during horse-back riding activities”; by Wesley H. Singleton, 2001, MSU:

The main finding of this study was that:

“Mean rein tension values were not statistically different between groups. Additionally, judge’s or rider’s subjective evaluation of lightness did not correlate with actual measurements of mean rein tension”.

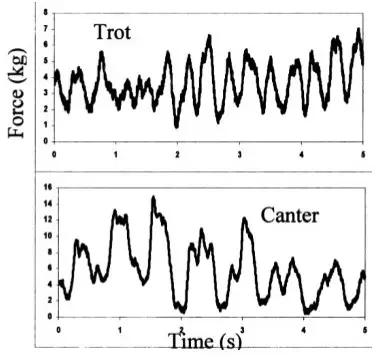

This study further went into detail of changes in pressure peaks which are reviewed next.

Changes of pressure peaks

# peaks per second: 3-trot; 2-canter

Note: Number of peaks in 5 seconds: trot: ±15 (180 per minute): canter ±9 (84 per minute)

“The magnitudes in this study are within a similar range to those reported by Preuschoft. The maximum forces shown in the graphs presented by Preuschoft (1999) are 30 N at the walk, 80 N at the trot and 60 N at the canter. In our study rider one was usually below such values while rider two exceeded those values during most of the trials.

The maximum value at the walk performed by rider one was 20 N while rider two reached 40 N. At the trot rider one reached maximum values of 45 N while rider two exceeded 90 N. Canter maximums rarely reached 75 N for rider one with most of the trials averaging a maximum tension of 50 N, while rider two occasionally reached 150 N”.

Although the rider perceived a constant rein tension, in walk there were regularly occurring spikes with a frequency of 108 per min, in trot 168 spikes per min and in canter 90 spikes per min”.

“Horse–rider interaction”; by Agneta Egenvall, Anna Byström, Michael Weishaupt and Lars Roepstorff; Veterian key; Chapter 15;

“Some studies have presented forces in weight units, but for the sake of comparison we have here assumed that 1 kg (weight) equals 9.8 N (force).

In pioneering work, it is stated that unexpectedly large rein forces were found, 5–75 N, up to maximal 150 N, on each rein. Most riders, using double bridles, used forces of around 5 N at halt increasing to 20 N at canter (Preuschoft et al., 1995).

In further work, different types of riders were compared (Preuschoft et al., 1999). Very low rein tensions were found for western riders, for riders riding only on the curb and at a few dressage stables where forces registered below or just above 20 N, when performing demanding exercises.

In other dressage stables, mean forces ranged from 59 to 147 N, without any difference between single and double bridles. Peak force during regular work was below 49 N in driving horses, 98–176 N during dressage training rising to 245 N when slowing down from canter. In trotters moving at high speed, forces up to 392 N were found (Preuschoft et al., 1999)”.

Rein pressure is also the consequence of the type of bit and riding style. Curb bits when used in Western riding are usually loose and tight for braking and turning. Snaffles are usually for continuous contact.

Why are auxiliary reins used?

Many riders from a broad range of different riding disciplines use short reins and have heavy hands. When reins alone don’t work, riders often resort to auxiliary aids, including draw reins, side reins, martingales, tight nosebands, extreme bits, etc.

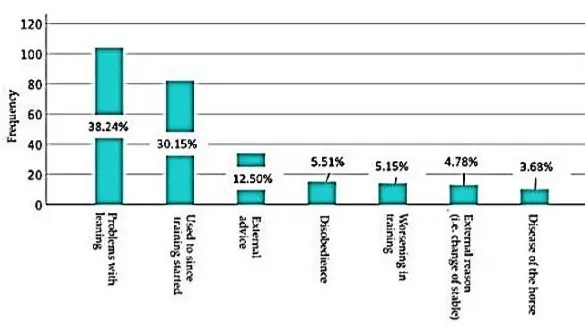

Auxiliary reins are used for a variety of reasons which are listed next.

Frequency of reasons for the use of auxiliary reins

“Evaluating Horse Owner Expertise and Professional Use of Auxiliary Reins during Horse Riding”; by Heidrun Gehlen 1,* , Julia Puhlmann 1, Roswitha Merle 2 and Christa Thöne-Reineke 3 Animals 2021, 1 Equine Clinic, Veterinary Department, Freie Universitaet Berlin, 14163 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 2 Veterinary Department, Institute for Veterinary Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Freie Universitaet Berlin, 14163 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]

The right rein pressure-what is the way forward?

There have been many studies published in the last 10-15 years which have addressed the issue of rein tension. While they have identified variations in the overall level of rein pressure and some of the conditions which create it, none have provided a satisfactory resolution as to its cause. This is the outcome of various factors, including experimental study design, inadequate study objectives, incorrect methodology/tools or incorrect insights. Quotes in the next two posts will reveal this state of affairs.

Some researchers have even gone so far as to propose eliminating the use of bits altogether. This may work for some and has undoubted benefits for the horse’s mouth. However, this is an extreme solution which will not be practical for many/most riders/trainers. Some studies have investigated the horse’s leg actions and tried to link them to the effects of tension variations, but their analyses have left a number of key questions unsolved.

The horse’s dynamics are misunderstood

The reason why this is the case is that the main problem lies in a misunderstanding of the horse’s dynamics. Riders both need to understand and respect these dynamics and show this understanding through more tolerant reins. This does not mean that they will lose the ability to collect the horse and to lower its standard of performance. On the contrary, they will be able to obtain it, but in combination with improved suppleness and positive attitude from the horse.

This adaptation would go a long way to resolving the welfare and performance issue. The mechanics of this adaptation lie at the heart of Equinamity’s new patent. Some general comments on these dynamics follow.

All actions of both the rider and the horse involve physical dynamics.

These dynamics must be integrated between horse and rider.

All planned actions are initiated by a sitting rider holding the reins.

Reins are a control mechanism for the rider.

Rein pressure reflects horse and rider characteristics.

All movements require a mobile head and neck.

A mobile head and neck requires rein flexibility.

The position of the horse’s head and neck reflects the nature of a movement, its complexity and the combined skills of the horse and rider.

The more the head and neck are fixed in one position by unforgiving reins the greater the negative consequences imposed in the rest of the horse’s body.

Repercussions will be shown through physical issues such as stiffness and diminished mobility as well as psychological issues such as disobedience.

Rein pressure should aim to be soft, yet firm throughout the movements.

Achieving this requires an intimate understanding of the horse’s dynamics.

Improved rein tension with flexibility will require a new and higher level of skill and coordination from the rider.

Some specific actions by the horse which will affect rein pressure are described next. Key portions of this list have been removed since they are contained in the patent application presented by Equinamity and wil be released at the appropriate time.

In most cases an action by the horse will be catalysed by the head and neck.

This head and neck action will involve a sideways twist, an upward, downward, or inward movement.

When the horse wishes to move, it must generate impulsion.

Rein pressure is maximized at a certain phase of the leg action.

Rein pressure is minimized at a certain phase of the leg action.

There is an important sequence of functional dynamics which needs to be explained in detail enabling the horse and rider to implement the new findings. This sequence is a fundamental component of Equinamity’s new patent application.

The solution that Equinamity has developed is a revolutionary new approach. It is so unique that it has been formulated as a patent and legal protection is being obtained. Consequently, the intellectual property it contains needs to be kept confidential for the time being and will be released at the appropriate time.