Equi-note 21 Hyperflexion-rollkur can damage the horse's neck causing osteoarthritis

Source: Library.academialberti.de

Equi-note 21

Hyperflexion-rollkur can damage the horse’s neck causing osteoarthritis

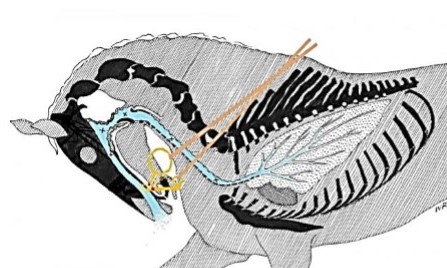

Previous posts have referred to damage created by constricting the trachea. This affects the horse’s ability to breathe and has an effect on the speed of the airflow. However, in addition, there are further areas where damage can occur.

This post refers to damage of a more structural nature, which occurs to the cervical joints themselves. While jumping and dressage are very different sports, considerable overlap exists in the training methods. Especially when it comes to rein length and rein pressure.

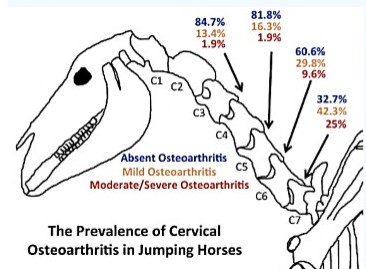

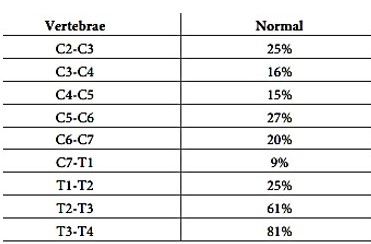

The following image shows where one researcher identified the location of cervical osteoarthritis in jumping horses.

Prevalence of Cervical Osteoarthritis in Jumping Horses

Source: Espinosa-Mur P, Phillips KL 1, Galuppo LD 1, DeRouen A, Benoit P, Anderson E, Shaw K, Puchalski S, Peters D, Kass PH 1, Spriet M 1. Radiological prevalence of osteoarthritis of the cervical region in 104 performing Warmblood jumpers. Equine Vet J. 2021 Sep;53(5):972-978. doi: 10.1111/evj.13383. Epub 2021 Jan 11. PMID: 33174228; 1-School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California, USA.

“Background: Cervical osteoarthritis (OA) has been documented as a potential source of pain and poor performance in sport horses.

Conclusions: This study showed that, although there is a range of interpretation of radiographic findings of the APJ, OA of the caudal cervical region is not rare in performing sound Warmblood jumpers. This suggests that OA in the caudal cervical region may be of low clinical significance”.

It is puzzling that such a widespread and debilitating condition could be described by the above authors as having “low clinical significance”. And one which damages many horses.

This comment is even more bizarre when in the first paragraph, they state that OA is a “potential source of pain and poor performance”. It was already well known that this is a very serious, complicated and debilitating issue for a variety of reasons. Part of its complication arises from the fact that in some cases it has been found that osteoarthritis occurs naturally. It is further complicated by the fact that there are many types and degrees of severity.

In addition, researchers have identified serious short-comings in research techniques and equipment used to obtain radiographs. These have created misleading results.

By way of example the above study used radiographs which the authors themselves admitted did not have orthogonal views. A number of research studies have pointed out the limitations of radiographs. One of which is quoted below.

Very different results were obtained by anatomic analysis of the bones themselves as described next.

“Characterization of bony changes localized to the cervical articular processes in a mixed population of horses”; by Kevin K. HausslerID1 *, Roy R. Pool2 , Hilary M. Clayton3 1 Gail Holmes Equine Orthopaedic Research Centre, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, United States of America, 2 Texas A&M University, Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, College Station, Texas, United States of America, 3 Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, United States of America; Published: September 26, 2019.

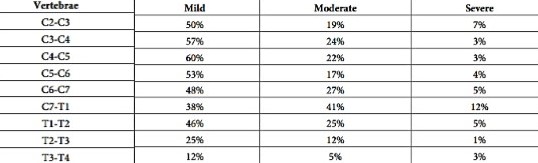

“Data were analysed to compare alterations in joint margin quadrants, paired articular surfaces within a synovial articulation, left-right laterality, and vertebral level distributions. And to determine associations with age, wither height and sex. Seventy-two percent of articular processes had bony changes that were considered abnormal.

Osteophyte formation was the most common bony change noted. Overall grades of severity included: normal (28%), mild (45%), moderate (22%), and severe (5%). The highest prevalence of mild changes was localized to the C3-C6 vertebral levels; moderate changes to C6-T2; and severe changes to C2-C3 and C6-T2.

Review of the equine literature suggests that cervical vertebral myelopathy is one of the primary disease processes affecting the equine cervical region. Concurrent osteophyte production has also been reported in studies on cervical vertebral instability. However, enlarged or encroaching articular processes associated with osteoarthritis are often considered a secondary contributing factor to spinal cord compression; rather than as a primary disease process”.

Vertebral level distribution of the osteoarthritis by articulation

Degrees of severity by articulation

Source: “Characterization of bony changes localized to the cervical articular processes in a mixed population of horses”; by Kevin K. Haussler

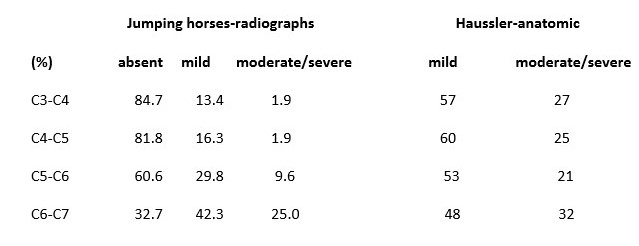

The following statistics show a comparison between these two approaches.

The only joint which shows a semblance of similarity is in C6-C7. This is all the more reason why the following quote on the limitations of radiographs is important:

“Radiographic anatomy of the articular process joints of the caudal cervical vertebrae in the horse on lateral and oblique projections”; by J M Withers 1, L C Voûte, G Hammond, C J Lischer 1Weipers Centre for Equine Welfare, University of Glasgow, Bearsden Road, Glasgow G61 1QH, UK. EQUINE VETERINARY JOURNAL Equine vet. J. (2009)

“Plain radiography is the standard imaging technique for investigation of diseases associated with the articular process joints (APJ) of the caudal neck; however, the radiographic anatomy of these structures on both lateral and oblique radiographic projections has not previously been described in detail.

Plain radiography is the primary imaging modality utilised in routine screening for osseous abnormalities of the cervical spine in the horse and a standard technique has been described previously (Whitwell and Dyson 1987; Butler et al. 2008). Routinely, this is performed with the horse standing and is limited to lateral-lateral projections (Whitwell and Dyson 1987; Butler et al. 2008).

Interpretation of cervical radiographs can be challenging due to the complex radiographic anatomy and overlap of structures on either side of the neck. Furthermore, because radiographs are 2D presentations of 3D structures, clinically significant lesions may be inadequately visualised when radiographs are obtained in one plane only. This limitation is illustrated in the difficulty in detecting axial enlargement of the articular processes on plain lateral-lateral radiographs (Butler et al. 2008)”.

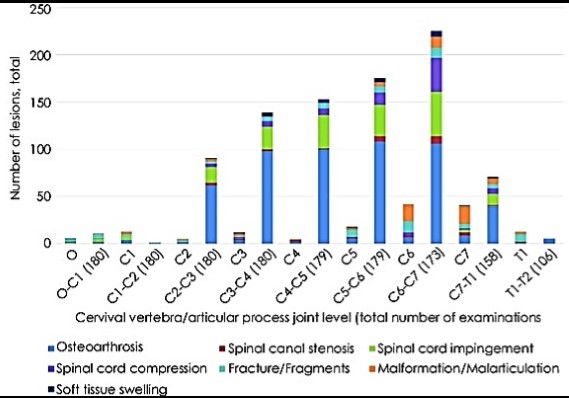

In addition, there are numerous possible causes of a cervical problem, as well as the possibility that a horse may have several problems at the same time, as the next chart shows.

Cervical vertebra-number/type of lesions

Source: “Computed tomography and myelography of the equine cervical spine: 180 cases (2013–2018)”, C. M. Lindgren, L. Wright, M. Kristoffersen, S. M. Puchalski; 2020, cc

There are also numerous types of osseous changes, as described next.

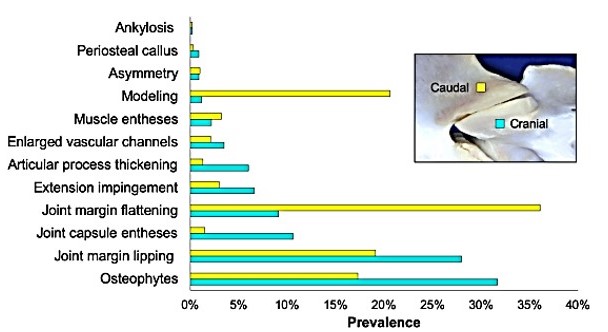

Prevalence of osseous changes

Note: Prevalence of the types of bony changes that are localized to the cranial (blue) and caudal (yellow) articular processes across all subjects.

Examples of osseous changes

Modelling

Flattening

Lipping

Osteophytes

Source: “Characterization of bony changes localized to the cervical articular processes in a mixed population of horses”; by Kevin K. Haussler, cc

For the concerned horse owner, how is it possible to identify if this problem exists in their own horse(s)? What are the symptoms? The following quote elaborates.

“Neurologic conditions in the sport horse”; by Daniela Bedenice,†, and Amy L. Johnson‡ † Department of Clinical Sciences, Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, 200 Westboro Road, North Grafton, MA 01536, USA ‡ Department of Clinical Studies, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, New Bolton Center, 382 W Street Rd, Kennett Square, PA, USA.

“Cervical Vertebral Stenotic Myelopathy/CVSM

CVSM primarily manifests as general incoordination or stiffness when the horse moves. Affected patients may trip, appear to lurch at the canter, have difficulty halting smoothly. And may swing out or collide their limbs while turning. Walking up and down hills can also be difficult for the horse. Most commonly, all four limbs are affected. But horses with milder disease can appear unaffected in the forelimbs, with mild signs in the hind limbs.

Additionally, it is common for hind limb abnormalities to be more obvious than those in the front. A long-strided stiff gait can be quite characteristic of the condition. But lower neck problems can also manifest as weakness in the front limbs. These signs include a short-strided, choppy forelimb gait, limb buckling at rest or during movement, and muscle mass loss (atrophy). Signs are often symmetric or mildly asymmetric, with the left and right side usually being similarly affected.

Signs of neck pain are inconsistent

Young horses with malformations frequently do not appear uncomfortable. Whereas older horses with lower neck arthritis can show mild to severe signs of discomfort. These signs include abnormal head and neck posture, most commonly carrying the head lower than normal. Or decreased range of motion when asked to bend to the side or raise and lower the head. More severely affected horses rarely bend their necks, even when asked to circle. And display a rigid “weathervane” posture when moving. If nerve root compression is occurring, the horse might show a front limb lameness that cannot be localized by a lameness examination. And become occasionally “stuck” with the head and neck held in an abnormal, usually lowered, position.

Abnormal muscling might be evident

Some horses have poorly developed neck muscles, while others seem to have poor topline muscling that extends to their rumps. Not every horse with CVSM shows overt signs of neurologic disease or neck pain.

In some cases, the first sign of the problem is a behaviour change under saddle, such as bucking, bolting, rearing, or stopping at fences. The horse might be resistant when working in one direction, reluctant to move forward, reluctant to bring its head and neck up into a frame. Or just lose enthusiasm for its job. Difficulty with bending or lateral work, often worse in one direction, and mild front limb lameness can be observed.

The rider might notice an occasional stumble, or the horse might have fallen under circumstances where it was not expected. Some horses have difficulty traversing hills but work well in other situations. The rider might comment that the horse feels lame, or different, but no apparent lameness is present. Obviously, many other orthopedic or even systemic problems can cause similar signs and poor performance.

Summary

Many performance problems that are noted by the rider could stem from CVSM. And horses without an obvious lameness or other explanation should be assessed carefully for neurologic disease and neck pain.”