Equi-note 16 Hyperflexion-rollkur increases the horse's conflict behaviour

Source: photos #1 & #3: dressagehub; wp: photo #2: @SymbolsOfSaturn129; nkc

Equi-note 16

Hyperflexion-rollkur increases the horse’s conflict behaviour

How does this come about? To begin with forcing the horse’s head and neck into a contrived position causes stress. The horse reacts by showing its discomfort in a variety of ways. The following quotes reveal some further aspects.

“Learned helplessness” by Dr. Ulrike Thiel, published in St. Georg magazine 2005:

“Under Pressure-The body language of the horse reveals much about his state of mind. It is possible to recognise whether a horse has completed its dressage training mentally relaxed and balanced. Or if it had been simply placed under pressure and has had to learn not to try to help itself.

The physical posture and facial expression of the horse, the movement of the ears and the expression of the eyes provide information about its well-being or discomfort. This assumes that the person can understand the body language of the horse.

Put another way: some physical positions into which the horse is placed put it into a particular mental state. For this reason classical training considers it to be particularly important that the rider, with his seat and aids, doesn’t disturb the horse or cause it pain. But brings it into positions in the movement in which it feels comfortable. It should be in balance, not only physically but also mentally”.

A further analysis is shown next which uses the method of an ethogram.

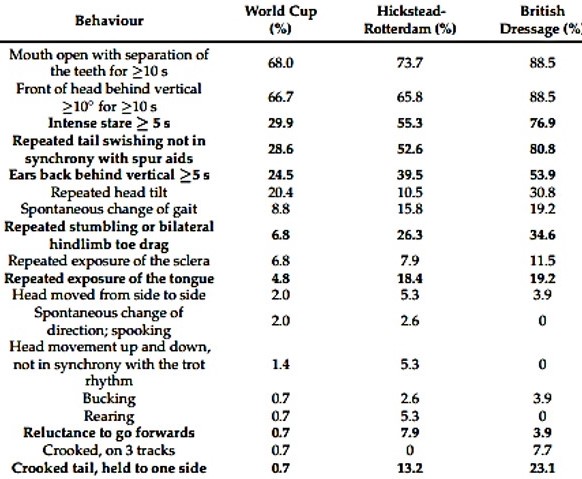

Source: Dyson, S.; Pollard, D. Application of the Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram to Horses Competing at the Hickstead-Rotterdam Grand Prix Challenge and the British Dressage Grand Prix National Championship 2020 and Comparison with World Cup Grand Prix Competitions. Animals 2021, 11, 1820. https:// doi.org/10.3390/ani11061 20

“Simple Summary: The Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram (RHpE) comprises 24 behaviours. The majority of which are at least 10 times more likely to be seen in a horse with musculoskeletal discomfort than a non-lame horse. A RHpE score of eight or more indicates the presence of musculoskeletal pain. The most frequent RHpE score for 147 competitors at World Cup Grand Prix events from 2018 to 2020 was 3/24 (range 0–7). This ndicated that the majority of horses were working comfortably. The aim of the current study was to apply the RHpE to 38 competitors at the Hickstead-Rotterdam Grand Prix Challenge. And to 26 competitors at the British Dressage Grand Prix National Championship in 2020.

The most frequent RHpE scores were 4 (range 0–8) and 6 (range 1–9), respectively. These scores were significantly higher than the World Cup competitors. This was associated with a higher prevalence of lameness and gait abnormalities. Which were shown in canter and more frequent errors in passage and piaffe, canter flying changes, canter pirouettes and rein back in the non-elite horses compared with the World Cup competitors. There was a negative correlation between the RHpE scores and the judges’ scores. Appropriate investigation and targeted management of horses with musculoskeletal discomfort may enhance both their performance and welfare”.

“Equine athletes: psychology and performance”: by Laura Jones, Sue Dyson; May 2016:Vet Times; https://www.vettimes.co.uk

“Although the role of psychological stress in horses is unclear, chronic stress has been implicated in many deleterious conditions. These inlude gastric ulceration, colic, recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis, decreased growth rates and reduced reproductive capability.

Correlations between heart rate, heart rate variability, behaviour scoring parameters and stress have been identified in ridden horses. Heart rate variability has been used as a measure of shifts in para sympathetic and sympathetic influence on heart rate during times of stress. This applies both in humans and in horses undergoing low-intensity, non-ridden exercise.“

“Indicators of stress in equitation”; by U. König v. Borstel, Department of Animal Science, University of Göttingen, Albrecht-Thaer-Weg 3, 37075 Göttingen, Germany, E.K. Visser Horsonality, Skipper 3, 8456, J.B De Knipe, The Netherlands, C. Hall, School of Animal Rural & Environmental Sciences, Nottingham Trent University, Southwell, Nottinghamshire, NG25 0QF, UK May 2017

Particular attention has been paid to short-term effects

Heart rate variability parameters reflect in theory more closely sympathovagal balance compared to cortisol levels

“Prevalence of Different Head-Neck Positions in Horses Shown at Dressage Competitions and Their Relation to Conflict Behaviour and Performance Marks”. Kienapfel K, Link Y, Konig v. Borstel U (2014)PLoS ONE 9(8): e103140. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.010314

“Much controversy exists among riders, and in particular among those practicing dressage, regarding what can be considered an ‘‘appropriate’’ Head-Neck-Position (HNP). The objective was to assess the prevalence of different HNPs in the field, the behavioural reactions of horses during warm-up and competition rides in relation to HNP and the relation between HNP and marks achieved in the competition.

Horses (n = 171) were selected during dressage competitions according to their HNP (3 categories based on the degree of flexion), and their behaviour was recorded during 3 minutes each of riding in the warm-up area and in the competition. Scans were carried out on an additional 355 horses every 15 minutes to determine the proportion of each HNP in the warm-up area. Sixty-nine percent of the 355 horses were ridden with their nasal planes behind the vertical in the warm-up area, 19% were ridden at or behind the vertical and only 12% were ridden with their nasal plane in front of the vertical. Horses carrying their nasal plane behind the vertical exhibited significantly more conflict behaviours than horses with their nose held in front of the vertical.

Horses were commonly presented with a less flexed HNP during competition compared to warm-up

A HNP behind the vertical was penalised with lower marks in the lower but not in the higher competition levels. Competitors in higher classes showed more conflict behaviour than those in lower classes. In conclusion, dressage horses are commonly ridden during warm-up for competitions with their nasal plane behing the vertical.”

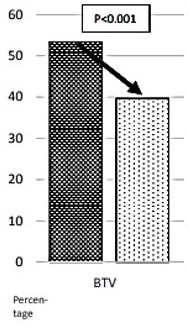

“Comparison of the Head and Neck Positions in Ridden Horses Advertised in an Australian Horse Sales Magazine: 2005 Versus 2018″ Bornmann, Tanja; Williams, Jane; Richardson, Karen Published in: Journal of Equine Veterinary Science Publication date: 2020

“Analysis of combined data from years 2005 and 2018 showed 47.0% (n=570) of the horse sample population were advertised with HNPs BTV. BTV HNP was observed as the predominant HNP (57.8%) (n=268), in the warmblood/eventers/show/performance (WESP) category.”

It is also important to note that betwen the years shown in the above image that a substantial decline in the numbers of horses behind the vertical has taken place as awareness of this problem has increased. This is confirmed in the next image.

Percent of horses BTV-behind the vertical 2005 vs 2018

(n-268 in 2005 and 303 in 2018)

“Towards a more objective assessment of equine personality using behavioural and physiological observations from performance test training”, Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2011, by U. König v. Borstel, G.A. Universität Gottingen, Dr. S. Pasing, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, M. Gauly, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano:

“Current definitions of horse personality traits are rather vague, lacking clear, universally accepted guidelines for evaluation in performance tests. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to screen behavioural and physiological measurements taken during riding for potential links with scores the same horses received in the official stallion performance test for rideability and personality traits.

Using the coefficient of determination, regression analysis revealed that about 1/3 of variation (ranging between r = 0.26 “constitution” (i.e. fitness, health)) and r = 0.46 (rideability)) in the personality trait scores could be explained by selecting the three most influential behaviour patterns per trait. These behaviour patterns included stumbling (with all traits except character), head-tossing (temperament, ride-ability), tail-swishing (willingness to work), involuntary change in gait (character) and the rider’s use of her/his hands (constitution, rideability), voice (temperament) or whip (constitution)”.

Examples of these forms of disobedience are shown next.

Three main forms of “disobedience”

Head tossing

Tail swishing

Stumbling

Sources: top photo: wikimedia.org. cc; photo in middle: wikipedia.org. cc; photo on bottom: racingTV. wp

The above photos are examples of each of the three conditions. They are not meant to indicate that this behaviour is exclusively the consequence of rollkur. These conditions can frequently have more complex origins.

Rollkur is used in a number of different disciplines

A great deal of attention has been placed on dressage horses. However, it is important not to omit the treatment that jumping horses have also been subjected to. The following images show that jumpers also receive rough treatment. However, it also needs to be pointed out that jumping is a strenuous and demanding sport, but of a different type. It involves many rapid changes of speed and direction. Accidents and stressful situations often happen. The author is by no means suggesting that they are always the consequence of rollkur.

Jumpers are also subject to stress

Source: equinamity.co

These extracts confirm that an extensive number of studies have been conducted which

evidence a wide range of the problems associated with rollkur

It should be noted that there are 166 studies quoted in the references in the above studies. Most of these studies have been conducted during the last 20 years as awareness of this problem has grown.

As a result of the strenuous nature of many equine sports, it is difficult at times to separate the physiological from the psychological effects.

However, the above studies have shown that it is entirely possible to distinguish the causes. This will enable firm conclusions to be drawn by owners, trainers and riders for the benefit of improved horse welfare.

This will become a major focus in subsequent blog posts.