Equi-note 23 Hyperflexion-rollkur-can damage the horse's teeth

Source: left photo: dianefollowell.com; middle photo: horseproblems.com.au; right photo: [email protected].

Equi-note 23 Hyperflexion-rollkur-can damage the horse’s teeth

The effects of rollkur have been explored in terms of body nand mental health and also in terms of vision. There is another key area which refers to its teeth. That is the subject of this post.

This is a difficult issue to try and pin exclusively on the rollkur problem. This is because tight nosebands, ill-fitting tack, hard hands and unstable rein contact can also have a negative effect on teeth. And these may or may not be associated with rollkur.

However, there are several items which have a particular relevance to rollkur. These are the sustained use of hard hands and short reins. Which force its head position backwards so that its jaw is virtually touching its chest. Consequently, the next quotes will look at research which has explored this matter further.

“Mouth Pain in Horses: Physiological Foundations, Behavioural Indices, Welfare Implications, and a Suggested Solution”; 2020 by David J Mellor Animal Welfare Science and Bioethics Centre, School of Veterinary Science, Massey University, Palmerston North 4474, New Zealand; [email protected]:

“Mouth pain in horses, specifically that caused by bits, is evaluated as a significant welfare issue. The conscious experiences of pain generated within the body generally, its roles, and its assessment using behaviour, as well as the sensory functionality of the horse’s mouth, are outlined as background to a more detailed evaluation of mouth pain. Bit-induced mouth pain elicited by compression, laceration, inflammation, impeded blood flow, and the stretching of tissues is considered.

Observable signs of mouth pain are behaviours that are present in bitted horses and absent or much less prevalent when they are bit-free. It is noted that many equestrians do not recognise that these behaviours indicate mouth pain. So that the magnitude of the problem is often underestimated. The negative experiences that are most responsible for welfare compromise include the pain itself. But also, related to this pain, potentially intense breathlessness, anxiety, and fear.”

Signs of mouth pain

Source: photo on left: canstockphoto.com; middle photo: pixabay; right photo: nkc

The hyper-sensitive bars

Source: madebyjessy.com, wp.

The following quote comes from the Riding Warehouse:

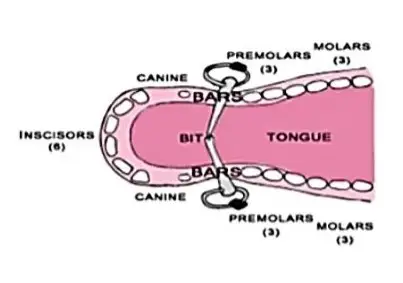

“The bars of the horse are part of the interdental space, an area of the horse’s mouth with no teeth. The space between the incisors and premolars is what makes it possible for a horse to hold a bit. The bars are the lower, or mandibular, part of the interdental space, and are extremely sensitive because they contain many nerve endings. Some bits employ bar pressure, as seen with single-jointed snaffles. Other bits wrap around the bars, as seen with wide-ported bits, to reduce bar pressure”.

Horse’s mouth structure with snaffle bit

Source: riding warehouse- wp

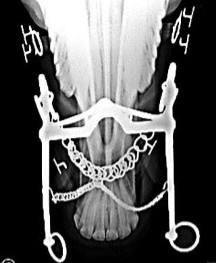

The effect of a curb bit is shown next. Because it is not jointed in the middle, it applies pressure on both sides of the horse’s mouth.

This bit obtains leverage with the reins attached to the small rings on the base of the shanks. When these are pulled by the rider the shanks rotate towards itrs chest, which means that the curb chain tightens against the underside of the horse’s jaw. To avoid pain from this action, the horse lowers its head and pulls its jaw inwards towards it chest.

X-ray of horse’s mouth with double bridle-snaffle plus curb bits

The bars are the most likely part of the horse’s jaw to be damaged. This is not only because of the jaw structure, but also because this is where the maximum leverage of the bit, reins and rider’s hands converge.

This next rollkur group of photos shows a very different style, in which the horse’s head is deliberately compressed towards its chest using maximum rein pressure. As the above research shows this is where maximum pressure is applied to the bars.

Extreme pressure applied by rider’s reins

Source: nkc

Other groups are dedicated to sports which require the horse’s head to be “fixed” at a higher level by use of a check rein. This rein is attached to the mouth, then goes over the poll and back to the withers. These include mainly trotting racers and carriage horses.

Head and neck compression is also obtained with a check rein

Source: photo on left: Pauli Impola in Tuomola, K., Mäki-Kihniä, N., Valros, A., Mykkänen, A., and Kujala-Wirth, M. (2021) “Risk factors for bit-related lesions in Finnish trotting horses”. Equine Vet J. 53: 1132- 1140. doi: 10.1111/evj.13401; photo in middle: Ajspeight on flickr; photo on right: nkc.

There are other sports involving abrupt and often violent manoeuvers with changes of speed and direction. In these cases the head and neck position will vary greatly. The best riders will achieve these dynamic changes with fluency and harmony. Whereas the less able riders will usually resort to abruptness and violence (perhaps unintended). This situation is most applicable to jumping, polo, eventing and numerous Western style sports.

Rapid dynamic changes in some sports are often very harsh

Source: photo on left: wikimedia commons, oa; photo in middle: writingofriding: 2enr: photo on right: author.

What is important to remember is that these positions are the result of specific sport demands. In most cases they should not last for more than an instant. And therefore are not intentionally designed to damage the horse’s welfare.

At the other end of the training spectrum are those horses which have been schooled with regularity and precision. And according to a set of defined classical principles. In the cases shown next they are dressage horses of the highest calibre having achieved worldwide distinction several decades ago.

Regrettably information at this time on tooth condition as a consequence of bit use did not exist. However, a harmonious attitude of the horses is clearly expressed in spite of the same tack as shown above.

Harmony can still be obtained with same bridles

Source: photo on left: pd; photo in middle: pd; photo on right: thecrazydolls.

It is not only at the highest training and showing levels that harmony needs to be expressed.

The next three photos show horses at intermediate level. They have snaffle bits and dropped nosebands.

The rider’s hands are gentle and the reins are soft. As a result, the horses are relaxed, working with suppleness and enthusiasm.

As noted above, in the wrong hands these same working tools can be damaging.

Soft hands and soft reins encourage cooperation

Source: author

The negative side to rein abuse needs to be explored further.

The source for the next quotations is: Nevzorov Haute Ecole, Equine Anthology, 2009, Forensic Medical Examiner’s office, St. Petersburg; email: [email protected].

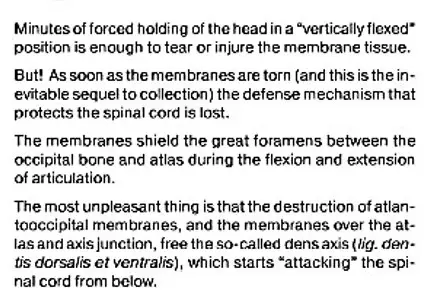

Excessive head flexion tears membrane tissue protecting the spinal cord

Aggressive rein action can cause bits to create hematomas on the bars

Rein pressure on the bars can be very high

Such exaggerated rein pressure can also lead to nerve damage and broken jawbones

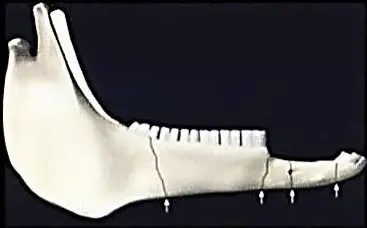

The main locations where the horse’s jawbone gets broken

Source: “Management of equine mandibular injuries” by W. H. Tremaine; equine vet educ. 1998.

In addition to fracturing the jaw and causing nerve damage, there is also the strong possibility of teeth being broken and/or pulled out. The next photo shows such a case.

Fossilized example of jaw with lost teeth

Source: [email protected]. wp.

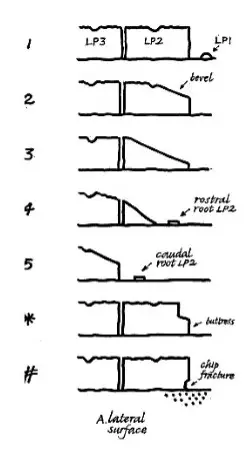

Continued rein pressure and rider’s arm action (such as sawing) will have an effect on the horse’s jaw. It is obvious that this will have a damaging effect on the teeth. Different types and degrees of damage are shown next.

Various features of bit-induced dental damage

Source: [email protected]. wp

“DAMAGE BY THE BIT TO THE EQUINE INTERDENTAL SPACE AND SECOND LOWER PREMOLAR” by W. Robert Cook Cummings, School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University, Massachusetts, USA, 2011:

“Veterinarians have often reported bit damage to the interdental space. Credit for the first research studies that focused on the interdental space are shared by an archaeologist (Bendrey 2007) and a team of veterinary anatomists (Van Lancker et al. 2007). Who surveyed osteological collections.

Bendrey found bone spurs on the interdental space in 87.5% of 32 working horses but in none of 28 Przewalski horses. Van Lancker et al found interdental space roughness in 48% of 87 warmbloods or trotters and 25% of 8 donkeys but only 7% of 68 zebra. No lesions were found in 3 Przewalski horses and 3 ponies.

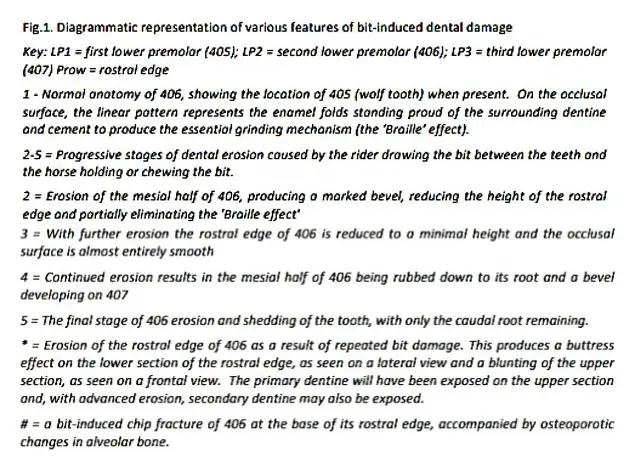

Equus caballus mandibles were surveyed in four museum collections

66 domestic horse mandibles were compared with 12 feral and Przewalski mandibles. Periostitis (bone spur formation) of the interdental space (bars of the mouth) was found in not less than 62% of the domestic hemi-mandibles. Erosion of enamel and dentine was found in 61% of the second lower premolars (Triadan 306 or 406). 88% of the domestic mandibles showed one or both lesions. The more severe the interdental periostitis, the more likely it was that the 06s were eroded. Twelve feral and Przewalski mandibles were free of both lesions”.

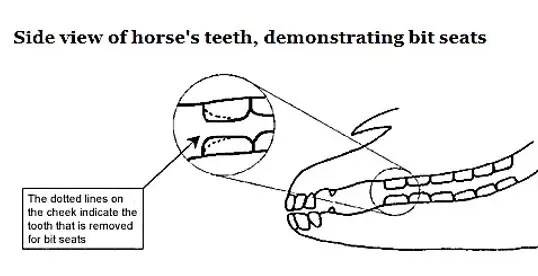

Much of this evidence has been used to argue for the elimination of bits altogether. However, this is unrealistic. It is essential to focus on the avoidance of abuse. Some excessive interventions have included: tooth removal (see Grisone); the actual removal of parts of the tooth so artificially creating “bit seats”. An example is shown next.

Removal of part of a tooth to create a “bit-seat”

Source: photo on left: carolinebagfeldt.se; photo on second left: mick field; third and fourth photos: Tuomola K, Mäki-Kihniä N, Kujala-Wirth M, Mykkänen A and Valros A (2019) “Oral Lesions in the Bit Area in Finnish Trotters After a Race: Lesion Evaluation, Scoring, and Occurrence. Front”. Vet. Sci. 6:206. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00206.

“Bit-related lesions in Icelandic competition horses” 2014; by Sigríður Björnsdóttir1*, Rebecka Frey2 , Thorvaldur Kristjansson3 and Torbjörn Lundström4 *1 Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority, Austurvegur 64, IS-800 Selfoss, Iceland; 2 Norsholms Djursjukhus, Biskop Henriksv 6, S-610 21 Norsholm, Sweden; 3 Agricultural University of Iceland, Hvanneyri, IS-311 Borgarnes, Iceland; 4 Djurtandvårdskliniken, Västra Husby, S-605 96 Norrköping, Sweden:

“Background

Oral lesions related to the use of the bit and bridle are reported to be common findings in horses worldwide. They represent an important animal welfare issue. In order to provide an overview of bit-related lesions in Icelandic competition horses, a field examination of the rostral part of the oral cavity was performed. This was done in 424 competition horses coming to the two major national horse events in Iceland in 2012. Records from repeated examination of 77 horses prior to the finals were used to assess potential risk factors.

Results

Mild lesions were recorded in 152 horses (36%) prior to the preliminary rounds. They were most often located in the commissures of the lips and the adjacent buccal mucosa (n = 111). Severe lesions were found in 32 (8%) horses. For 77 horses examined prior to the finals, the frequency of findings in the area of the mandibular interdental space (bars of the mandible) had increased from 8% to 31% (P < 0.0001). These findings were most often (16/24) regarded as severe. The presence of lesions on the bars was strongly associated to the use of curb bits with a port (OR = 75, P = 0.009).

A high frequency of severe commissural lesions has been reported in thoroughbred racehorses, most of which wear a snaffle bit. It has been suggested that this may be a result of abrasion against the second upper premolar tooth, especially if the tooth has a rostral enamel overgrowth. It is clear that the oral commissures and the bars of the mouth are susceptible to injury in sport horses. And that further information is needed to determine the precise cause and nature of these injuries”.

“Pre-Competition Oral Findings in Danish Sport Horses and Ponies Competing at High Level” 2020; by Mette Uldahl 1, Louise Bundgaard 2, Jan Dahl 3 and Hilary M. Clayton 4,* 1 Vejle Equine Practice, Fasanvej 12, 7120 Vejle Øst, Denmark,;2 Louise Bundgaard, Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Agrovej 8, 2630 Taastrup, Denmark; 3 Jan Dahl Consult, Østrupvej 89, 4350 Ugerløse, Denmark; 4 Sport Horse Science, 3145 Sandhill Road, Mason, MI 48854, USA:

“This study addresses the presence and location of lesions in the corners of the lips, inside the cheeks, and on the bars of the mouths of 342 dressage, show jumping, and eventing horses. They were examined by a veterinarian before competing in the Danish National Championships in 2020.

At the corners of the lips, external ulcers were correlated with internal ulcers, and both were associated with scarring and depigmentation. The anatomical location of an ulcer is relevant when addressing causation, with differences being reported for those at the oral commissures, the bars, and the buccal mucosa. Lesions in and around the lip commissures have been described frequently and have been related to the use of snaffle bits, which is not surprising since this is the most commonly used bit in Europe. Jointed snaffles act primarily on the commissures and the tongue.

Tight nosebands

have also been associated with commissural lesions perhaps related to holding the bit up into the commissures. Lesions of the bars have been related (Animals 2022) to the use of a curb bit with a port that circumvented the effect of the tongue in protecting the bars or an unjointed snaffle.

Other studies indicated that ulcers occurred primarily in horses competing at a high level in the disciplines of dressage, eventing, Icelandic competitions, trotting races, galloping races, and polo. These findings are supported by our findings in the subpopulation of dressage ponies, where the frequency of ulcers was 26.4% for Category I, which is the highest level, 8.7% for category II, and 0% for category III”.

Erosion/contusion at the lip commissures and ulcers of the buccal mucosa were associated with similar lesions on the bars. If dental hooks or sharp enamel points were recorded on one side, they were likely bilateral. Dental findings were associated with scarring/depigmentation but not with mucosal ulcers or erosion/contusion at the lip commissure.

Horses examined immediately after a competition

Oral lesions were visible in 9.2% of 3,143 Danish horses across all disciplines and levels of competition. But with a higher frequency in horses competing in higher level competitions and in dressage.

In 208 Finnish event horses, 52% were found to have acute lesions after completing the cross-country phase. In both studies, the inner lip commissure was the most common lesion location.

Due to the morphology of the cheek teeth, the mechanics of chewing, and the nature of the diet, horses tend to develop sharp enamel points along the buccal edge of the upper cheek teeth. In addition, an enamel overgrowth (hook) is often present on the rostral edge of the upper second premolar. It has been hypothesized that the lip commissures may be crushed between the bit and the rostral part of the second premolar and that the buccal mucosa can be compressed against the cheek teeth by a tight noseband, leading to abrasion by sharp enamel points. Buccal ulceration or evidence of previous ulceration adjacent to upper cheek teeth was reported in 94% of ridden Swedish horses.”

“Bit-Related Injuries in Harness Racehorses” y Kentucky Equine Research Staff:

“Researchers examined the mouths of 261 trotters, including 151 Standardbreds, 78 Finnhorses (a native lightweight draft), and 32 ponies, for bruises and wounds immediately following a race. They looked at specific bit-contact areas: the inner and outer corners of the lips, bars of the lower jaw, cheek tissue near the second premolar tooth, tongue, and roof of the mouth.

The researchers then collected information about the type of bit used for each horse, making special note of the thickness and composition of the mouthpiece. Details of other equipment were taken, when applicable, including the use of an overcheck, jaw strap, or tongue-tie. Past racing history was mined from a reliable online database.

Injuries were observed in 84% of the horses in the study

Regardless of the type of bit worn, half of those were classified as moderate or severe. Five horses (2%) had visual blood outside of the mouth from the wounds”.

The following quote indicates another important reason why buccal problems are neglected.

“Incidence and Severity of Abrasions on the Buccal Mucosa Adjacent to the Cheek Teeth in 199 Horses”; by T. E. Allen at the AAEP Annual Convention, Denver, in 2004 by American Association of Equine Practitioners:

“Most horse owners and trainers were unaware that their horses had buccal abrasions and other dental abnormalities, disproving the common misconception that dental disorders in horses usually cause weight loss, quidding, difficulty eating, and other obvious behavioral problems”.

The evidence shown above clearly indicates the fragility and sensitivity of the horse’s mouth. It must be treated with great care and maintained both with good dental treatment and optimum communication between rider and horse.

Equinamity’s proposed solution of using the reins more flexibly will go a long way to resolving this knotty problem. This is because it is not based on hard, fixed hands. If riders and trainers reflect deeply on this, they will realize that a fundamental new principle is needed. This vital information is going to be revealed by Equinamity in a later blog post.